Edwardtide Digital Pilgrimage

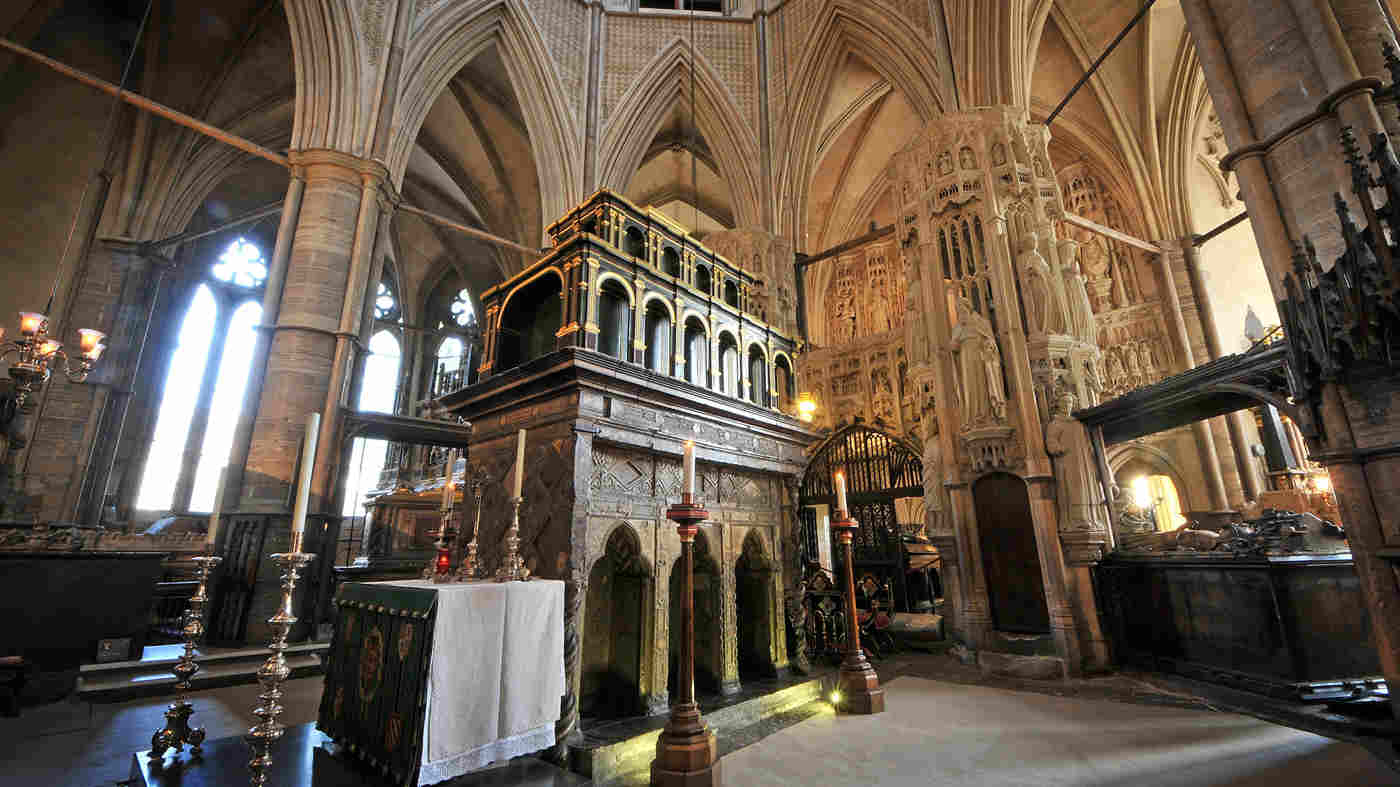

On Saturday 18th October, pilgrims will visit Westminster Abbey to remember the life and legacy of Edward the Confessor. Edward's Shrine lies at the heart of the Abbey, and pilgrims throughout the centuries have found themselves there, kneeling in the stone niches to pray. This year, you can participate from wherever you call home.

Although you may not be able to join us in person this year, we want to invite you to partake in this digital pilgrimage around Westminster Abbey during Edwardtide (13th -20th October 2025).

Make yourself a cup of tea, and find a quiet space. We recommend having a pen and paper nearby. You also may choose to light a candle or do something else to help yourself enter into this time.

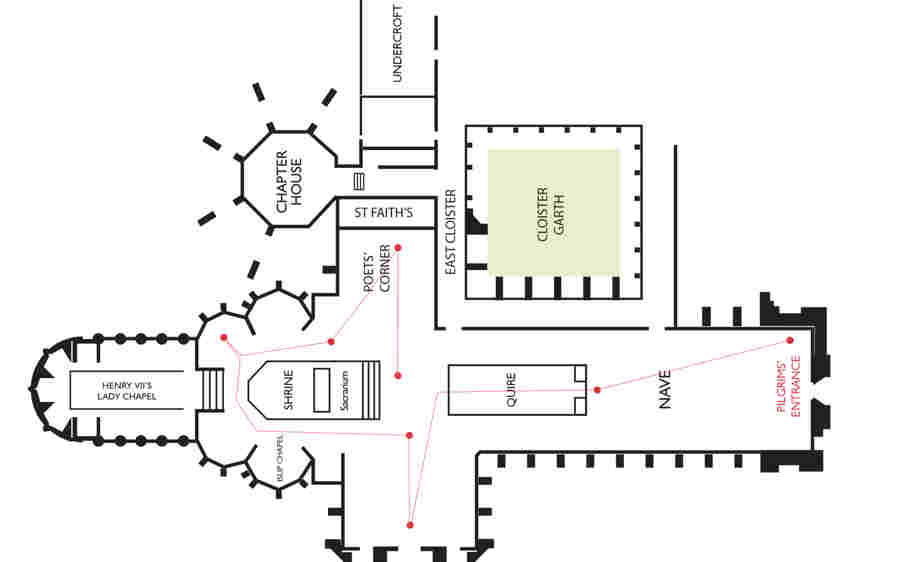

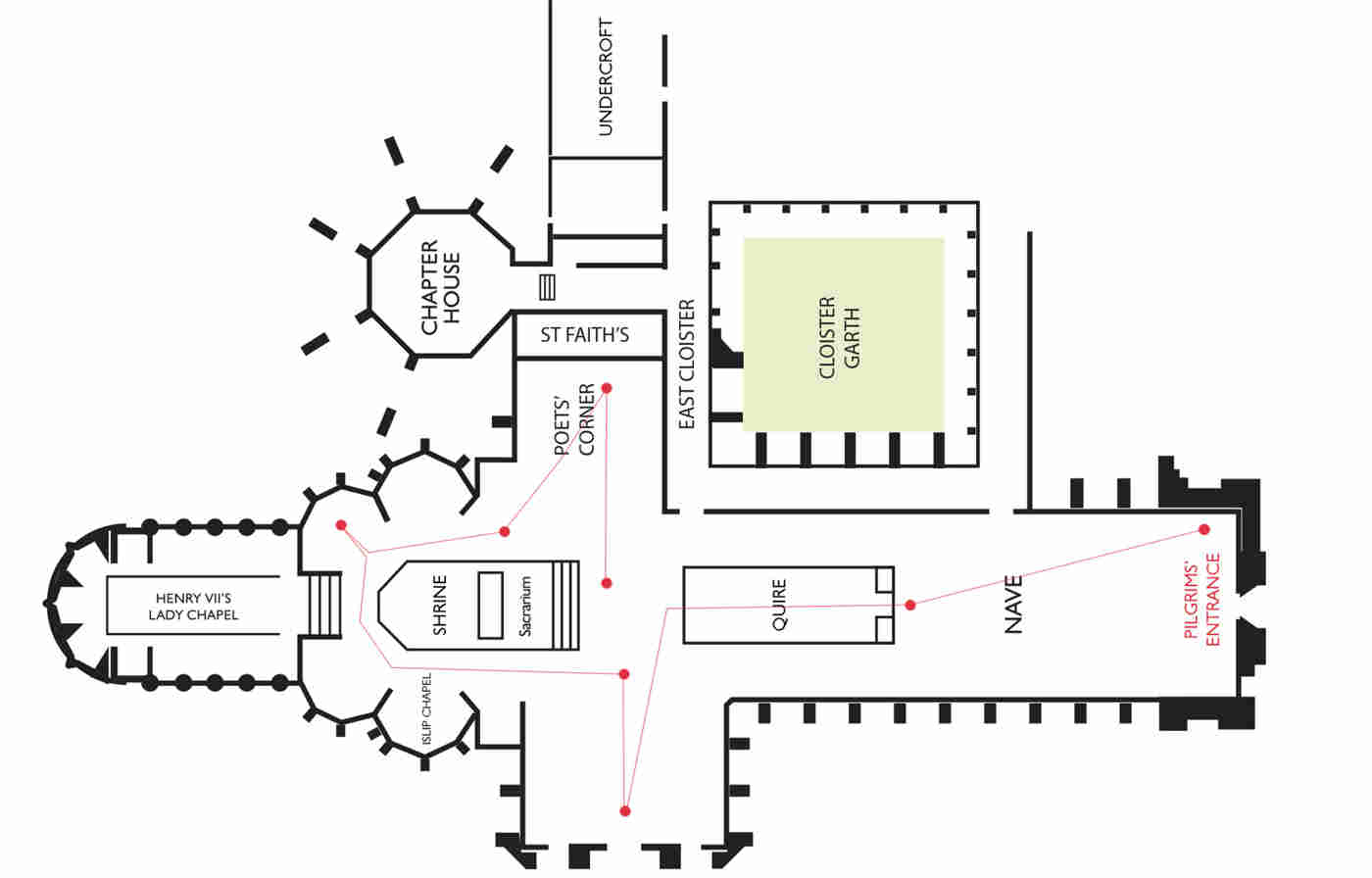

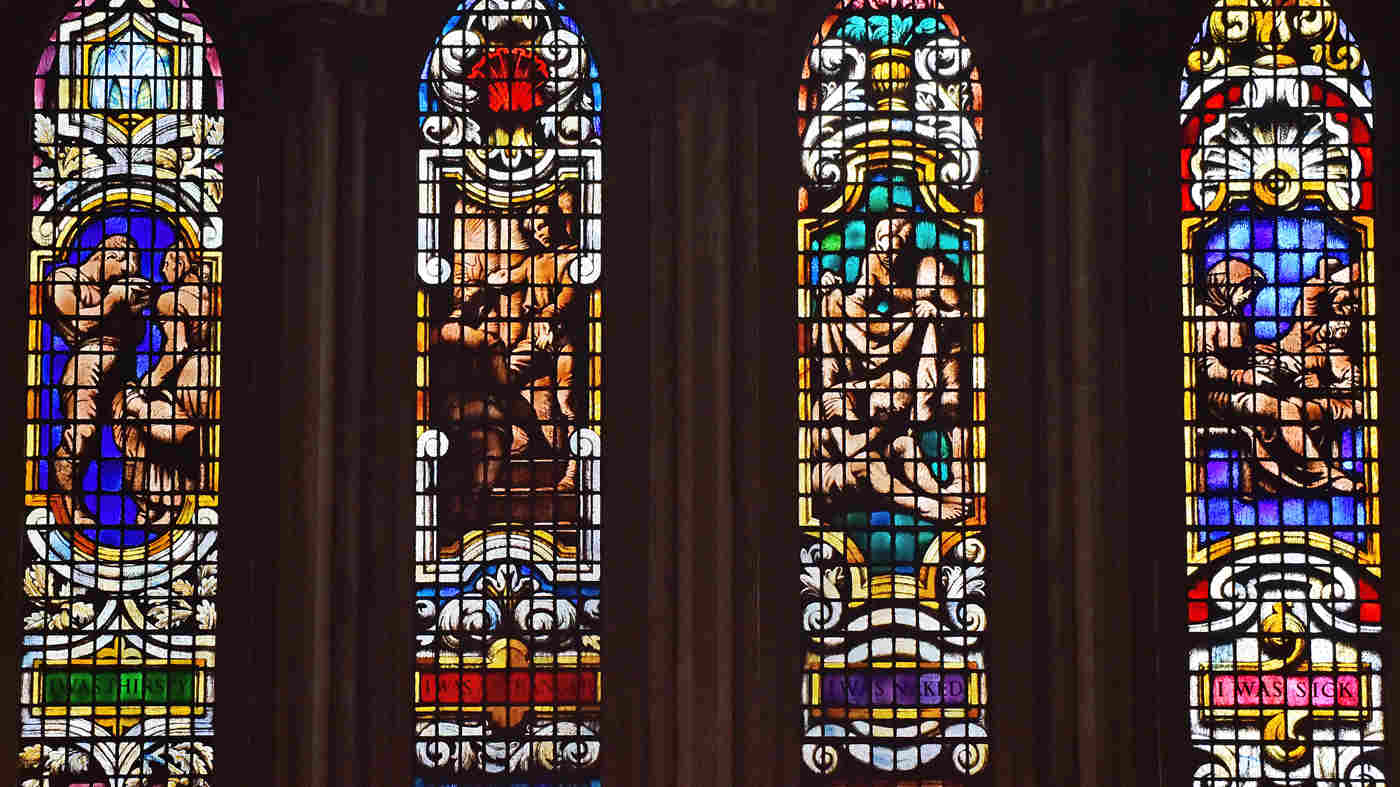

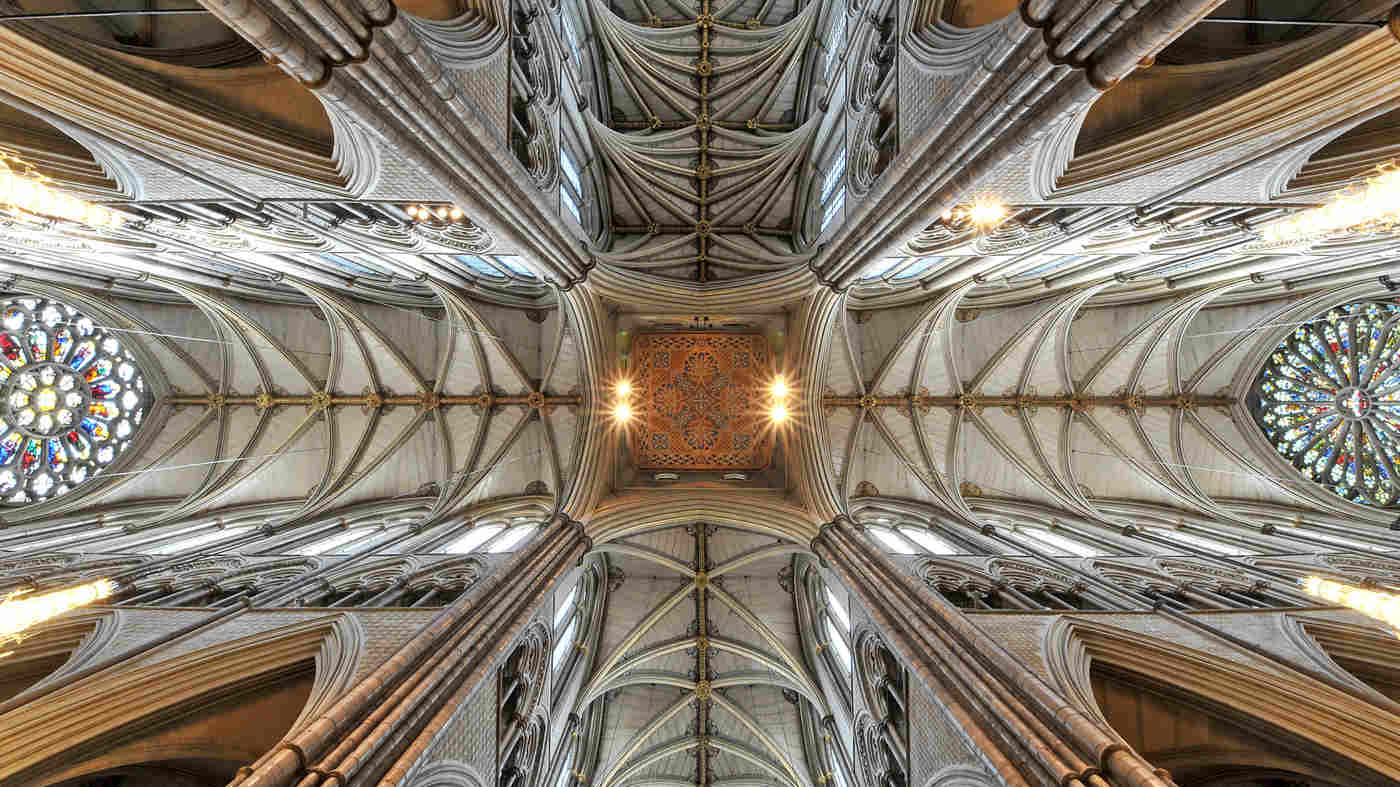

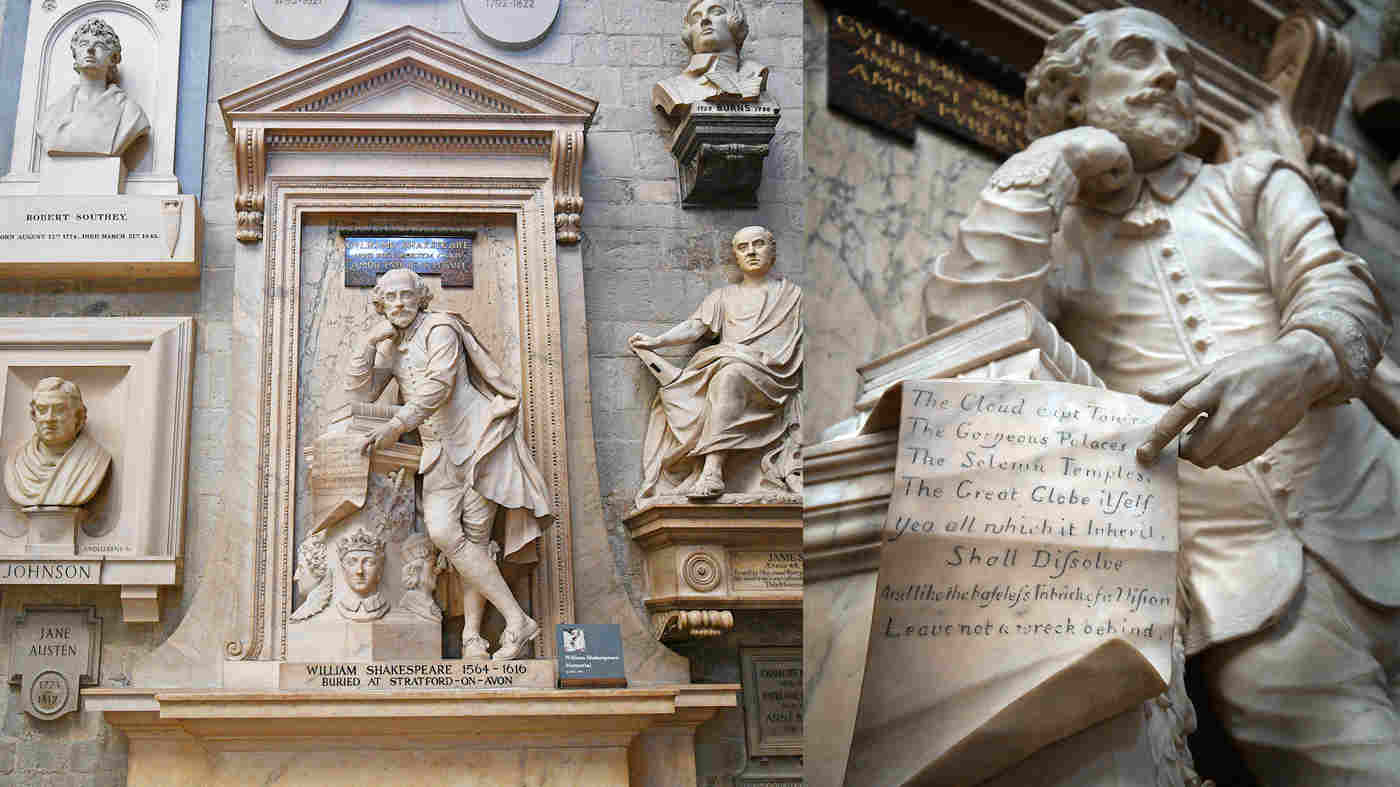

As you scroll, you'll find a series of images, poems and prose, and reflections which will transport you around Westminster Abbey, following in the footsteps of pilgrims today to reflect on Edward's life.

Finally, you'll be invited to share any reflections you have at the end of the pilgrimage.

Thank you for joining us on pilgrimage.